Article begins

August 9, 2016, was a good day for Phil Heasley, the CEO of a financial services company in Florida. Fishing with his crew of three off the coast of Maryland from his 68-foot luxury yacht, Kallianassa, he caught a white marlin that was six feet long and weighed 76.5 pounds. Heasley was competing in Ocean City’s annual White Marlin Open competition, the world’s largest billfishing tournament. His was one of 1,389 white marlin caught during that year’s competition, but was the only one to clear the 70-pound minimum that conferred eligibility for the prize. That meant that he got all the prize money—all $2.8 million.

August 22, 2016, was a bad day for Phil Heasley. That was the day the organizers of the White Marlin Open informed him that he would not get the prize money after all—because he had failed a lie-detector test.

Fishing competitions are notorious for inciting cheating, and they can be hard to police directly. Hence the reliance on polygraph testing. In this case, more than 300 boats were competing over an area of several hundred square miles, and there were strict rules to follow: boats were not to leave the harbor before 4 a.m., not to put their lines in before 8:30 a.m., not to keep them in after 3:30 p.m., and not to fish more than 100 nautical miles from Ocean City, Maryland. And while a crew member could hook the fish, the registered fisher was to fight it alone—no easy task for a man in his 70s, as Heasley was. (This “hook and hand” rule was unusual: fishing tournaments usually stipulate that the same person must hook and fight the fish.)

Heasley and his crew members all failed the polygraph. Kallianassa’s captain offered the memorable excuse that he failed because he had drunk so much and taken a lot of cocaine at a celebration the night before the polygraph test.

In May 2017, my research assistant Dana Burton and I sat through a nine-day trial at the US District Court in Baltimore, watching Phil Heasley challenge the validity of the polygraph test he had failed so as to reclaim the $2.8 million snatched away from him. The expert witnesses included the resident of the American Polygraph Association and the editor of Polygraph, the official journal of the American Polygraph Association. They testified on opposite sides of the case.

***

The polygraph—the lie-detector machine—took shape in the 1920s and 1930s in the United States, where it had three fathers. John Larson, the first US police officer to also have a doctorate, worked for the Berkeley police department, where he had a reputation as a liberal reformer. He developed his lie-detection machine as an objective scientific replacement for the crude methods of violence and intimidation regularly used by police officers to extract confessions from those they “knew” to be guilty. The machine made its public debut in 1921, when he used it to investigate thefts at a Berkeley sorority. However, the thefts continued after the woman identified as the culprit left the sorority, and she would later recant her confession, attributing her suspicious physiological reactions during the test to a repressed history of sexual abuse. In later life, Larson would turn against his invention, calling it a “Frankenstein’s monster.”

By then, however, Larson’s protégé, Leonarde Keeler, had refined Larson’s invention (adding a roll of unfurling paper inscribed by mechanical pens as well as a capacity to measure perspiration) and energetically promoted it. He persuaded banks that it would help them identify employees who embezzled. He also worked for the US government, polygraphing German prisoners of war during World War II, as well as hundreds of employees of the top-secret uranium production facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

William Moulton Marston, the most colorful of the polygraph’s co-inventors, developed a slightly different machine around the same time. He has recently come to popular attention thanks to a lurid but learned biography by Jill Lepore and a racy Hollywood biopic. A feminist avant la lettre, he lived openly with two women, Elizabeth Holloway and Olive Byrne. He was also the creator of the cartoon character Wonder Woman, transmuting his frank appetite for bondage and domination into a key trope, the “lasso of truth,” in his cartoons. His advocacy for the polygraph backfired when he testified in defense of James Frye, a Black man who had recanted a murder confession. Marston said the polygraph showed that Frye was telling the truth when he said he was innocent of murder. In what is widely recognized as one of the most important judicial decisions of the twentieth century, establishing what became known as “the Frye standard,” the DC Court of Appeals ruled against Frye and Marston in 1923, saying, “while courts will go a long way in admitting expert testimony deduced from a well-recognized scientific principle or discovery, the thing from which the deduction is made must be sufficiently established to have gained general acceptancein the particular field in which it belongs.” Since then, with certain limited exceptions, polygraph evidence has been banned in US courts.

The polygraph prospered despite the Frye setback, however. By the mid-1980s, two million Americans a year were being polygraphed, and a quarter of US private companies were using the polygraph to assess the honesty of their employees. The legal landscape changed in 1988 when the US Congress passed the Employee Polygraph Protection Act, forbidding the use of polygraph tests by private employers. However, polygraphers soon adapted, and there is plenty of work for them today. Currently, federal employees of the CIA, the DIA, the FBI, the NSA, and the nuclear weapons laboratories are regularly polygraphed; sex offenders often submit to frequent polygraphs as a condition of parole; and most police departments use polygraphers to screen potential recruits for past wrongdoing and to obtain confessions from criminal suspects. (The ban on polygraph evidence in court is easily circumvented: confessions are entered as evidence with no mention of the polygraph tests that produced them.) Meanwhile, private polygraphers, who do not require a license in some states, do contract work for police departments, offer marital fidelity testing, and are called in to adjudicate fishing contests.

***

I decided the best way to understand the polygraph was to become a certified polygrapher. For ten weeks, I spent nine hours a day, six days a week in a windowless polygraph training facility. My seven classmates were almost all police officers, two of them from Malaysia. My instructors, led by a former US Army interrogator, included a former FBI agent, police officers, and private polygraphers. We spent the mornings being lectured on various aspects of polygraphy and the afternoons practicing on one another. By the end of the ten weeks, I had been polygraphed about 60 times and had administered roughly 60 polygraph tests to my classmates. The class was harder work than any class I ever took at a university. I later took an advanced one-week class at a different polygraph school to get certified in the art of polygraphing sex offenders. In all honesty, I was the least competent student in either class, but I now have a framed certificate on my wall letting the world know that I am a qualified polygrapher.

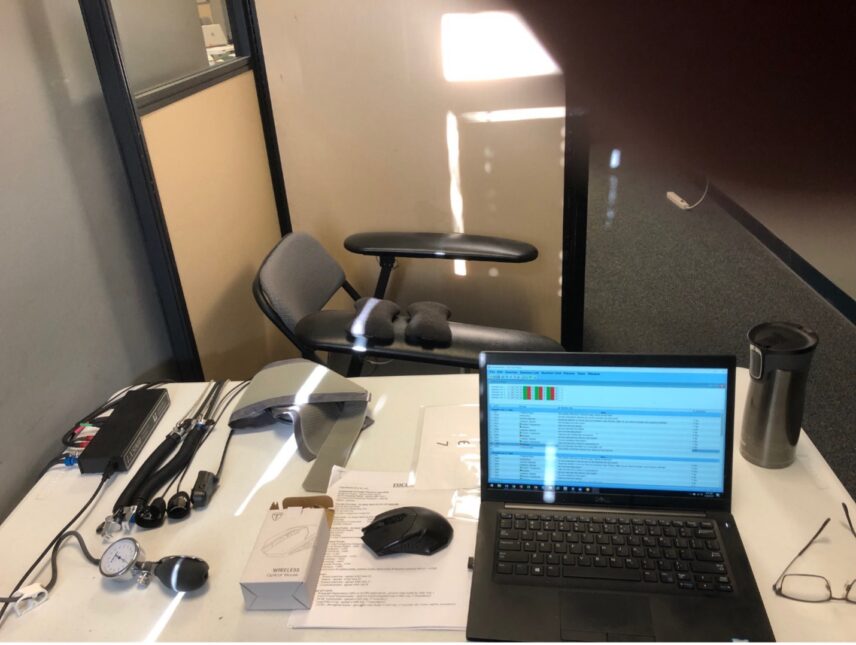

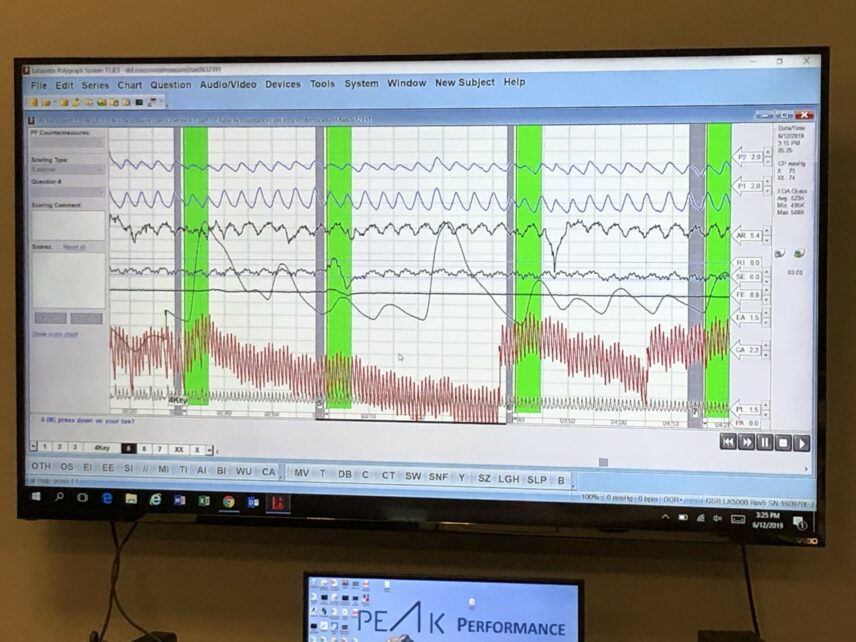

We began basic training by mastering the hardware. We learned how to gracefully fasten pneumatic tubes around a subject’s upper and lower chest to monitor their breathing, to wrap a blood pressure cuff around their upper arm (or sometimes the ankle) to record their heart rate, and to attach galvanometers to fingers to track changes in sweat response. These measuring devices are all plugged into a switchboard, which, in turn, is plugged into the examiner’s laptop, feeding it a constant graphic flow of bodily measurements. We also learned about hardware and observational practices that help detect attempted countermeasures by test subjects. (For obvious reasons, I will not describe them here, though I will give the free advice that it is pointless to put antiperspirant on your fingertips before a polygraph exam).

We then learned about question formats. “Screening tests” probe a subject’s past, while “diagnostic tests” investigate a particular event. The two kinds of tests require different questions, and the questions should be sequenced in particular ways. Some questions are designed to elicit what the polygrapher knows is a lie. Physiological responses to these questions provide a baseline—an image on a screen of that person’s individualized lie physiology—against which responses to other questions can be compared. Those questions, we were taught, must then be sharply focused. Less “did you assault your wife?” and more “did you punch your wife in the face on March 6?”

But we spent most of our time on the complexities of scoring. We learned about the different scoring schemes used by various government agencies and schools of polygraphy, and we were drilled day after day on the intricacies of turning the graphic chatter on our computer screens into objective numbers expressing the likelihood that our subject was lying. Our computer software automatically generated these numbers for respiration, but we had to look closely at the wiggly lines on the screen to manually score sweat and heart rate with numbers that were then entered into a table. This involved strict rules for when a measurable response began and ended, and it often required the deployment of digital calipers to effect precise measurements. While my instructors scored polygraph tests with breezy efficiency, I struggled to apply the baroque scoring rules we were taught and dreaded having my scoring audited by classmates. To my annoyance, the Miami police officer who had never been to college kept finding errors in this professor’s scoring.

***

On June 14, 2017, Justice Bennett released his 52-page judgment in the case of White Marlin Open, Inc. v. Heasley. It is a complex document. Bennett reviewed at some length circumstantial evidence from the Kallianassas written ship logs and engine records suggesting that its crew violated the rules by putting fishing lines in the water before 8:30 a.m. He reviewed expert testimony by the editor of Polygraph magazine that the polygraphers erred by giving a “diagnostic” rather than a “screening” test and concluded he was wrong. He came to the same conclusion about the same expert witness’s opinion that questions such as “Did you, yourself, violate any fishing rules on Tuesday, August 9, 2016?” were vaguely phrased and caused “undue mental processing” that might look like a lie on screen. (Who am I to disagree with the testimony of the president of the American Polygraph Association? But I myself thought the question, which requires the test subject to have internalized the rules as common sense, was confusing and should have been phrased, “did you put lines in the water before 8:30 a.m. on August 9?”) Then, sweeping aside the expert witness who testified that the polygraph is not scientifically reliable, the judge averred that a contract is a contract and Phil Heasley had signed a contract to abide by the results of a polygraph test when he paid $30,000 to enter the contest.

In other words, the $2.8 million was the catch that got away from Phil Heasley.

Responding to the judgment with anger, Phil Heasley said, “I am not the kind of person to lay down and let anyone run over us with lies and junk science.” He appealed the decision to the appellate court—and lost there too.

Leonarde Keeler, imagining the replacement of juries by polygraphers, once said, “Someday I can picture a medical legal committee with no judges, no lawyers in particular, but instead some scientific experts who will examine suspects and render a decision as to their guilt and opinions of their personality. Such well-trained men can better judge the reactions and social possibilities of a man than a haphazard group of businessmen and lawyers.”

The utopian dream of the polygraph is to afford certainty in the face of deception, to make lies transparent. In this case, which featured the leading polygraphers in the land testifying against one another, the polygraph in many ways just deepened the mystery.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to acknowledge Dana Burton, who helped collect some of the information in this article and provided editorial feedback on the first draft.